So now, as we get close to the year's end, let's have one more look at the UK Labour Party's electoral performance, shall we? As you're aware, we've been tracking this in opinion polls throughout 2016, and on that measure there were some stirrings of life back in the spring, which faded over the summer and seem now to have dropped away precipitously - all fine gradations of unpopularity at a time when Labour has been lagging further behind than at any previous period it has spent in Opposition since 1945. Be that as it may, you're probably thinking 'polls, schmolls' and getting ready to say that they hardly seem all that accurate any more. There's a bit of truth to that assertion - polling is indeed getting harder - though we feel duty bound to point out that most polling still seems to be somewhere near the mark. National polling in last month's US Presidential election, for instance, was pretty much spot on, whatever the polling miss in relatively sparsely-surveyed Michigan and Wisconsin.

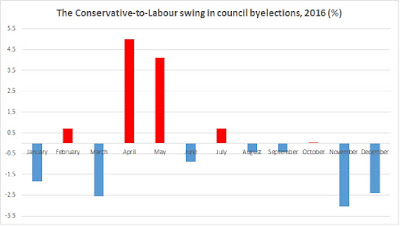

Well, there's another test for you - actual votes in actual ballot boxes, as the Liberal Democrats always used to say. And we don't just mean the May local and devolved elections, which went pretty badly for Labour everywhere outside London (and catastrophically in Scotland, where they fell to third place). There are actually local elections up and down the country almost every Thursday night, and occasionally there's an exotic Monday or Tuesday poll as well. What does the data on those reveal? Well, as you can see from the percentage numbers in Labour-versus-Conservative results (above), overall there's rather an even-steven feel to all this. If we take the 164 contests for which we can compare Labour and Conservative performance since the last Parliament - excluding, for instance, all those wards where one of those parties did not stand last time, or failed to put up a candidate on this occasion - there hasn't been a vast amount of swing in 2016. In fact, it's probably around only 0.5%, though the direction of travel is from Labour to the Conservatives - hardly an encouraging result for a party supposed to form the official Opposition, and facing an austerity government in its seventh year.

The swing towards the Conservatives has been gathering a bit of pace of late, too, as November and December appear to have been particularly bad months for Labour. That may be because there are problems with getting the party's vote out during the dark winter months. Turnout is very low, as it usually is at this time of year - particularly so in some Labour wards such as one in Lancaster covering the University, which turned in a seven per cent turnout last week. Yes, that's right, seven per cent. Overall, there was a three per cent and a 2.4% swing from Labour to the Conservatives in November and December, while those two big Labour data bars in April and May represent only a tiny number of contests - three and four, respectively. In sum, it's fair to say that on this front things have been pretty dismal for Labour, okay for the Conservatives (as they're the sitting government), but pretty good for the Liberal Democrats, who've gained a net total of 21 seats since May alone. So well done to them.

Coming back to Labour's performance, all this looks even less encouraging if we journey back to 2011 using Liberal Democrat data on contests from that year. We haven't been able to source perfect numbers on 2011, by the way, and we think that our series is a bit incomplete, so please do get in touch if you've got what you think is a complete dataset. But in any case, the orders of magnitude are clear: there was probably about a 5% swing from the Conservatives to Labour that year, over the same period in the last Parliament. That Parliament, need we remind you, ended in a very bad Labour defeat. So without looking at the opinion polls at all, we can easily see that Labour's performance is quite a lot weaker than it was in 2011, presaging perhaps a worse defeat in 2020 than the party experienced in 2015. They're doing better in London, by the way - there's a swing to Labour there of about two per cent - but given what we know about the urban nature of their remaining support and the results of the Mayoral election in London, that's not much of a surprise either.

This all fits with Labour's performance in Parliamentary by-elections held during 2016. That wasn't again too disastrous earlier in the year, with solid defences in Sheffield, Ogmore and Tooting. But recent performances have been very poor indeed, as Labour was squeezed into losing its deposit in Richmond Park and then humiliatingly pushed into fourth place in Sleaford. The first can be written off as the classic effect whereby a third party is pushed way down by tactical voting and a desire to kick the government where it hurts: the second was to be honest astonishingly bad, another indicator that Labour seems to be losing touch with whole swathes of the country. Sleaford was the strongest Conservative byelection defence since the early 1980s - more than thirty years ago.

The whole picture again looks even worse when we compare Labour's numbers to those from 2011. They had some really quite creditable performances that year, with for instance Debbie Abrahams elected in Oldham East and Saddleworth with a ten per cent increase in her party's share of the vote. Dan Jarvis won Barnsley Central with a 13.5% increase in Labour's vote there, and a 13.3% swing from the Liberal Democrats. And so on. This year? Not so hot. There was a bit of movement towards Labour in Sheffield Brightside back in May, but there was a slight swing against them in Ogmore, and the less said about Sleaford, the better. Yet again, only in London - in the Tooting contest triggered by Sadiq Khan's election as Mayor - did Labour turn in anything like the performance you might expect from the main Opposition party. If we exclude the Witney and Richmond Park byelections this year as not really comparable to the five 2011 contests, all of which saw Labour start in first place - and that's a very favourable assumption for the red side - then the same picture emerges as for local byelections. The average swing towards Labour, and away from their main rivals, in these votes was 5.3% during 2011; this year it's 2.5%. They're just not hitting even the 'heights' they reached under Ed Miliband.

Opinion polling tells us that Labour are way behind, at a time in the electoral cycle when they were a little bit ahead in late 2011. That's bad enough. But you don't need to listen to pollsters. The local contests held every Thursday night tell us the same thing, if perhaps in less stark terms. Parliamentary byelections confirm the picture. The difference between 2011 and 2016 doesn't look as bad when you look at these real votes as it does when you look at the polls, but there might be good reasons for that. For one thing, we've been looking here over a whole year - including a period in the spring when Labour's polling didn't look quite so miserable as it did both before and after that brief (and very limited) recovery. And for another, the government of the whole UK is not on the line in these local contests. The story from the ballot box looks, at the very least, compatible with the pollsters' numbers.

You don't require opinion polls to tell you that Labour's popularity in this Parliament stands some way below its scores during the last. The question then becomes: is anyone listening?